Your Garment Stories

S79MFRW

S – Organic Cotton Farming

The organic cotton bales to make the fabric for your shirt came from organic farms about 650 km away from Ahmedabad in the Akola region. Many farmers grow organic cotton in their small farms and they are managed and supported by Arvind Agribusiness, a part of one of the biggest Textile companies in India, Arvind Mills. What started out as a small project now encompasses more than 40,000 acres of farmland working with nearly 6,000 farmers!

Mayank Baheti, the project Head at their office said

“At Arvind, we have a simple definition of sustainable agriculture – MORE with LESS. More yield, income, confidence, transparency and traceability, less input cost, fossil energy, capital, and debt. No smokes and mirrors, and no exploitation of labour or the environment.”

Organic cotton farming is the process of growing cotton without the use of synthetic pesticides and chemical fertilizers. The only additives come in the form of manures, and the soil quality is controlled by crop rotation. The impact on the environment is reduced drastically, producing clean and safe cotton while creating a sustainable cycle. Organic farming is best suited for small and marginal farms.

“PAYMENT IN MY ACCOUNT WITHIN 7 DAYS!”

“I used to follow the conventional practices (using chemicals) of farming cotton for which my expenditure on fertilizer and irrigation were very high. The yield used to be good but input expenses were too high and there were no marketing system in place. Three years ago I started working with Arvind and adopted organic farming practices. Since then my expenditure on fertilizer and irrigation reduced drastically and the yield has improved significantly. I don’t even need to bother about selling the produce because Arvind buys directly from my doorsteps and deposits the money in my account.”

7 – Handspun by Spinners

The organic cotton bales were sent to a sliver making unit where the cotton was further cleaned and combed into long strands several times and slivers were produces for required yarn counts on machines. A Khadi co-operative, Udyog Bharati, based in Saurashtra region then distributed them to women artisans. Some of the women worked at the unit while some took them to their nearby village and spun them into hanks of yarns on hand operated Ambar charkha. Extra special care is taken while working with organic cotton. It is worked on in their unit in a designated area. Generally spinning in mill uses 50% of the energy – in the form of electricity – used in total fabric production. These artisan women worked by hand, without using any electricity and creating no carbon footprint!! Isn’t that amazing….?

One of them told us :“We use Ambar Charkha machines so that we can spin 8 to 12 yarns at a time. It needs skill and I have to be careful that I join the yarns when they break. The joint should be good so that it does not break again later and it should not show when the fabric is woven. ”

I have been spinning for four years now. I have learnt it well and I also teach others?! I like my work. The day passes when we have fun competitions…”

When the yarn is spun, after counting, it is tied in a certain way for ease of filling a beam for weaving later. Each pack of this counted yarns are called ‘Aanti’.

9 – Handwoven by Weavers

Each type of cotton growing in the farms has a specific quality that determines the elasticity, strength and thickness of the yarn it can produce. Each henk is made of 1000 meters of yarn. To produce fabric of different thickness and count of fabric, the thickness of each henk is different. To produce yarn of finer count, more expertise is required.

Organic henks – yarns counted, calculated and beams are hand filled and prepared. Bobbins are also filled. This process takes at least a week. It is now ready for weavers to weave the fabric.

After the spun yarns are received and paid for, they were then given to the weavers. Each weaver has a hand operated and paddle operated looms. First they roll the hanks on a big wheel called a beam. This is then attached to a loom and the weaver makes the cloth by inserting yarns backwards and forwards. Unlike mill fabric this weaving process is done by skillful hands and no electricity is used.

Do you know that the thousands of threads that go into making your shirt are hand counted and calculated many times by several artisans? This is how fabrics were made for thousands of years.

Meet one of the weavers Dhirubhai Solanki…..

“I work only in sunlight so that there are no chances of spoiling

the fabric by not seeing it properly!”

‘Namaste!’

My name is Dhirubhai Solanki and I am 50 years old. I learnt weaving from my father; I have been weaving since the past 35 years. I used to weave pure cotton handloom for the Khadi centre in Visavadar earlier and Bapunagar. I now weave for Gondal’s Udyog Bharti as they give me better wages. For the last two years I have been also weaving organic cotton. I earn around 5,000/- rupees a month. I begin my day at 6 AM. I weave from 8Am to 12 Pm and break for lunch and rest. I resume at 2:30 PM again and weave till 6:30 PM My family consists of five members, my wife, two boys, a girl and me. My daughter has studied till the 10th grade; she now helps me in my work.”

M – MORALFIBRE – Our Production Partner

Where Does It Come From? and MORALFIBRE (www.moralfibre-fabrics.com) have worked very closely together on this shirt production, which is our fifth together. Your shirt was created as a custom print design using the ‘ForteArts’ Logo.

MORALFIBRE is based in Ahmedabad in Gujarat and was set up by Shailini Sheth Amin to promote and source sustainable materials. The MORALFIBRE team organise the design, sourcing and production of the shirts – with tailoring taking place in their newly set up tailoring unit. Their ethos is sustainability with fairtrade and ethical production. They work with local co-operatives which provide fairly paid work for thousands of rural artisans in Gujarat. The work is de-centralized with the fabric production based in remote villages and undertaken by self employed artisans as part of the Khadi co-operative movement set up by Mahatma Gandhi as part of his goal to create an independent India.

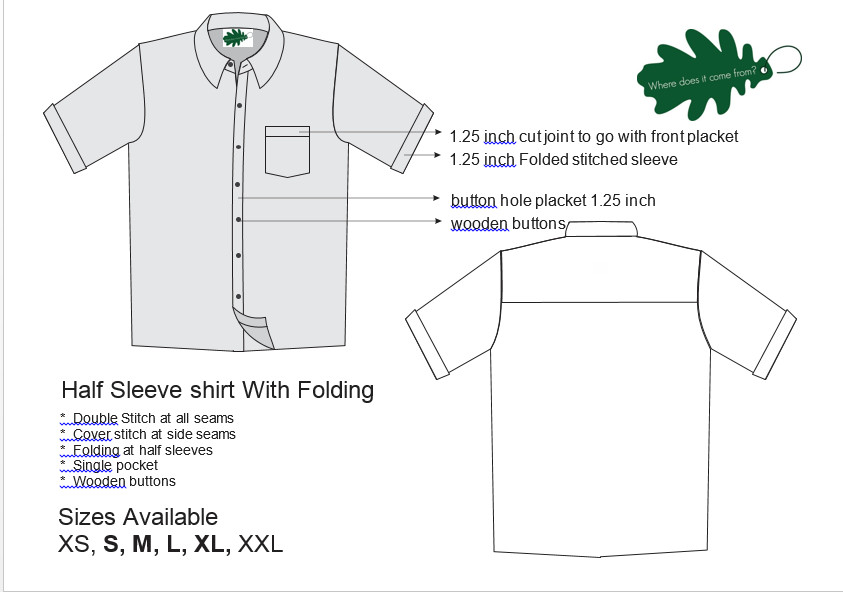

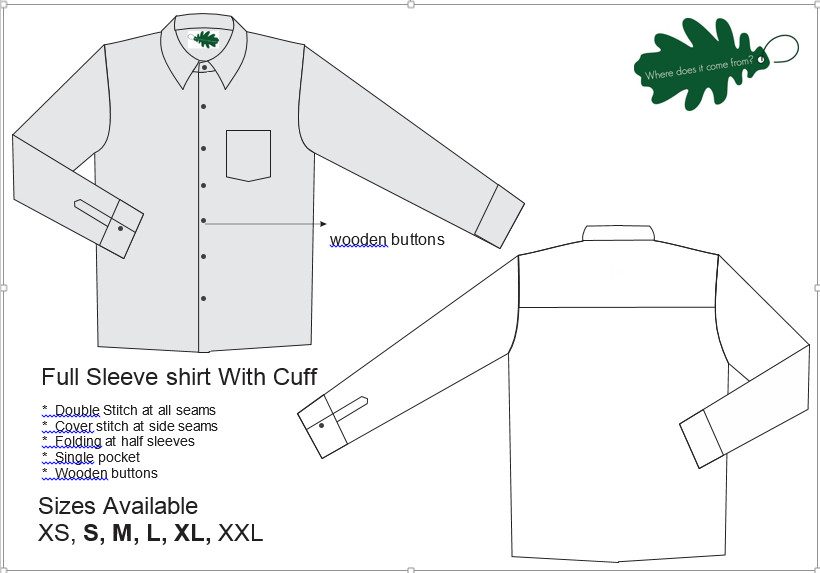

We worked together closely on the design of the shirts, ensuring that they would be comfortable, stylish and appeal to our customers. Jo from Where Does It Come From? specified the shirt requirements and colours were selected during her visit to MORALFIBRE in April 2016. Sanjay from MORALFIBRE was in charge of the shirt design process and after input from colleagues and Where Does It Come From? customers these designs were created.

The sustainability ethos is core to both MORALFIBRE and Where Does It Come From?

- – No electricity is used in fabric making – which makes the fabric virtually carbon neutral.

- – No heavy chemicals used – the fabrics are allergy free.

- – The traditional production technique use much less water (approximately one fifth) than standard mill processes.

- – There is minimal air, water and land pollution and no use of depleting fossil fuels.

Shailini with a group of weavers in a village, understanding and assessing their their skills and needs

Sanjay, the MORALFIBRE designer, came up with several design options which Jo from Where Does It Come From? discussed with the customer before the final design was selected. When approved the print design was then specified for the screen printers.

F – Hand Dyed and Block Printed

The dying of all fabrics was done by a traditional dyer. With the advent of mills these dyers are losing work. We believe in supporting these craft people who work on a smaller scale. This helps in preserving their craft, their skills and their dignity. Also our dyer is happy to dye smaller quantities at a time which works fine with us! We made sure he used the best quality dyes and other chemicals. Each colour is dyed differently and has different processes. Also colour fasting processes are very different too.

Meet your dyer:

“Salaam! I am Moyyudin. I work with my small team. I am from a Chhipa community, traditional dyer community well known for our dying craft and skills. I learnt it from my father and uncles. I come from a nearby region Rajasthan and I work in Ahmedabad for the last fifteen years. “

“With my traditional knowledge, experience and ready to try new things, we survive! No one can beat me in colour matching!”

The dyed fabrics are then hung high by Adil and Musa and dried in natural air in the shade – no electric dryers are used.

Unfortunately the team had already finished dying the fabric for your shirts when we arrived to interview them, so the fabrics you see in the photos are going to some other lucky customers!

Hand Screen Printing

We have used hand-screen printing method for this printing work.

The screens are made of nylon mesh with 200×200 tiny holes in every inch square. The pattern to be printed is drawn out in detail and to perfection on a butter paper first. Then it is exposed on the nylon screen in a darkroom and processed so that the perforations discharge required dye on the cloth. The screen is then fixed on a frame. The size of the image and frame can be as big as 45” to 60”, depending upon the size of the printing tables the unit works with.

For this design two separate screens were required – one for each colour – which had to be aligned. This requires special efforts and skills.

For this design two separate screens were required – one for each colour – which had to be aligned. This requires special efforts and skills.

We worked with Tahirbhai’s team for this project. Tahirbhai’s team have worked on most of the blockprinting for Where Does It Come From? – including the scarves and children’s shirts.

Meet Tahirbhai:

“I am Tahirbhai. Salaam Walaikum!

I hail from Rajasthan. We are five-generation block printer’s family, may be more but we do not have more concrete evidence of our family history!! My whole extended family is in this craft.

About fifteen years ago I moved to Ahmedabad, Gujarat to expand our work and try my luck. Ahmedabad is also a large printing hub of India. I moved to my uncle’s printing workshop based here. I took some time to understand the different taste in print design, colors etc. here. We used to work on export orders only whereas here there is a huge local market. Also the way of working: doing business was very different. After some time I started on my own. My expertise is in hand block printing. For hand screen-printing orders, I work with another printing unit.

Two years ago we had to close down our hand block-printing unit. The orders were slowing down. I was not sure whether to continue with hand block printing or to move to hand screen-printing?! MORALFIBRE got in touch with us just around that time. With orders coming in from them my work is continuing.We have a collection of over 5000 blocks and 600 screens. Unlike hand block prints, screens have to be cut up and destroyed after the job is done because storing large frame is a problem. I want to continue with this beautiful craft.”

R – Personalised Hand Tailoring (not Factory Mass Production!)

Rajubhai, the master tailor, has stitched your shirt. He has spent half his life in learning and mastering pattern making and the rest in tailoring and stitching, Today he is known as a master karigar (Artisan) because he can cut patterns as well as do the expert tailoring. Tailoring is his family’s profession for many generations but he has mastered it even more.

Rajubhai, the master tailor, has stitched your shirt. He has spent half his life in learning and mastering pattern making and the rest in tailoring and stitching, Today he is known as a master karigar (Artisan) because he can cut patterns as well as do the expert tailoring. Tailoring is his family’s profession for many generations but he has mastered it even more.

With factory based garment production these fine skilled tailors are losing work. Rajubhai says that, and it is widely known in the tailoring circle that once a tailor goes to work in a factory, he loses his craft very quickly. He gets to stitch a certain part – like a sleeve or a collar – hundreds of times and nothing else and that too very very quickly. The tailor becomes a ‘machine’ and not a skilled artisan any more. It is very important for us to support these artisans, their crafts and their dignity.

Rajubhai lives in small house with his wife and two children and tailoring is the only source of income for his family. His wife and a daughter assist him in buttoning and pressing the garments and other related chores. They have refused to get themselves photographed!

First Rajubhai cut the fabric according to the shirt design template and then it was printed. Then the printed fabric pieces returned to Rajubhai for stitching.

“ I like to tailor well and with full care, skill and attention. Once the pattern is cut and ready and I am set for my work on the machine, it takes me around 45 min. to stitch a shirt. And that will be a Top Class Job!

I enjoy working with you because you are after quality and fair remuneration. I can show my skills and you like my work.”

W- Where Does It Come From?

Hi I’m Jo, the founder of Where Does It Come From? – the clothing business that brings you ethical and traceable clothes. Currently based in Ipswich, Suffolk (UK) we work closely with our partners in India to create and develop the designs to ensure that the wonderful fabrics are made into garments that will work for you and your children. We hope that finding out about how your clothes were made and the people who made them will make you love them just a little bit more…..

From idea to business launch took two years, with launch happening in June 2014. You can read more in our Blog section, including newspaper and radio coverage. It’s been wonderful to be acknowledged for our work – 2016 brought us 2nd place in the ‘Greenest Product’ category at the Suffolk Green Awards (with a Highly Commended) as well as being selected as a Green 100 business – the top 100 ethical businesses in East Anglia.

Thank you so much for buying from us – the more we sell the more difference we can make. We have lots of plans for new designs, new partners and new projects so stick with us and together we can change the world!